A normal cervix and how to care for it

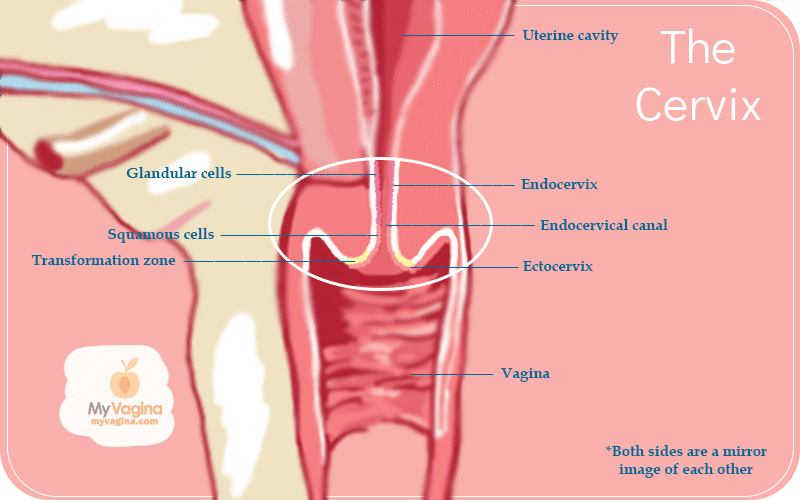

The cervix is the passage joining the vagina and uterus, made of cartilage, but with a thick layer of soft tissue encasing it. The cervix is about 4cm long but size varies with age and use, and individual variances.

The cervix is thought to be a sexually sensitive area, (theoretically) key in some types of orgasm. If you look at the cervix from the vagina, it looks like a doughnut.

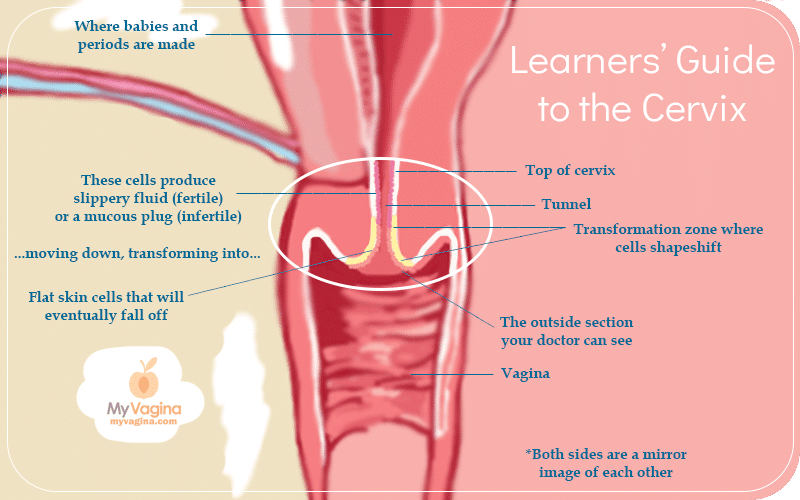

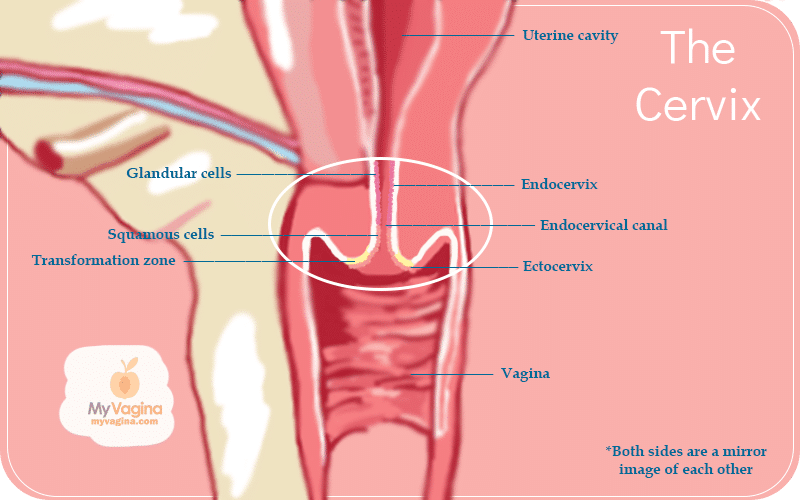

The hole in the middle of the ‘doughnut’ is called the cervical os, with the vagina-end of the cervix called the ectocervix, and the uterine side the endocervix. The middle part is called the transformation zone.

The length and appearance of the cervix changes with your menstrual cycle, while giving birth, and after birth.

The cervix is the gatekeeper to the uterus and is necessary to allow or block entry and exit where necessary. The cervix opens and softens during ovulation to allow sperm to enter, but other times stays hard and closed, only allowing menstrual blood out.

When a woman gives birth vaginally, the cervix opens very wide so the baby can fit through it.

Before puberty, the endocervix is in the vaginal area of the cervix (some cervix is inside the actual vaginal canal), but it sneaks up with age.

The transformation zone of the cervix

The transformation zone is easily torn, as it is only one cell deep, meaning it can bleed easily, even after sex.

The cells in the transformation zone produce some of the fluids of the menstrual cycle and have a high cell turnover, which can make them prone to some forms of cancers.

As a woman ages, her cervical cells tend to be the more durable squamous epithelial cells, instead of the mucous-producing columnar epithelial cells.

This change in cells contributes to lower vaginal moisture levels with age. It is now understood that the columnar epithelial cells are the hub of infection transmission.

Fluids, mucous, hormones and fertility and how they affect your cervix

The columnar cells produce mucous that either promotes or inhibits pregnancy1,2.

The size, texture and location of the cervix changes throughout the cycle, with the oestrogen surge just prior to ovulation causing the cervix to swell and soften, and the os (hole) to widen. This widened os allows sperm in, should there be any.

Fertile cervical fluid, released near ovulation, is alkaline, and slippery-smooth like egg-white, providing a safe passage for sperm to get to the viable egg and extending the fertile period for up to five days.

Once ovulation is over progesterone levels increase and cause the cervix to harden, become closed and produce thicker cloudy mucous, a plug. This plug keeps sperm and bacteria out of the possibly-pregnant uterus, and keeps it hard and closed to protect the foetus.

This mucous plug is one of the ways that artificial hormone progestin (in birth control pills) works, acting as a barrier method. It is also why if labour is induced, the cervix must be forced to soften or complications may arise.

Colour and appearance of the cervix

Red

The younger you are, the redder your cervix will look. This red is a different red to the red of inflammation or infection. Usually up to about 25-years-old, the colour is a deeper red.

Pink

A normal cervix sees several incarnations during a menstrual cycle in terms of how it looks and behaves.

A normal cervix is generally pink, smooth and shiny, more or less resembling your other mucous membranes, a la your mouth. This colouring is the same across the board of ethnicity, as we actually do all look the same on the inside.

The older you get, the paler pink your cervix becomes, however, those who are breastfeeding also have paler cervices.

Reddish-orange

At some parts of the cycle, a cervix may appear somewhat reddish or orange, and the cervical os (the middle of the hole) may be rough. This area is the transformation zone.

The tissue from inside the cervix makes up the endocervical canal. Sometimes hormones can cause the tissue to migrate to the outside of the cervix and appear to be making up a part of the cervix.

Reddish-orange tissues are therefore considered generally to be normal, along with the pink.

Blueish-purple

A bluey tinge is typical after 6-8 weeks of pregnancy and is called Chadwick’s Sign.

Why the cervix changes colour

The transformation zone can increase in visibility due to hormonal changes related to pregnancy, oral contraceptive pills, intrauterine devices (IUDs).

The cervix can also be more prominent while a speculum is inserted into the vagina, causing the cervix to pop out slightly. This popping out is called cervical eversion and the cervix should go back to normal as soon as the speculum is reversed back out of the vaginal canal.

The columnar epithelial cells will be darker than the other flesh around it and may have a grape-like or sea anemone look to it. There may also be blood vessels on the cervix surface.

Sex and orgasm and your cervix

Female sexuality is still a topic that is far from being fully understood, however, it is clear that the cervix may play a role in the female orgasm and sexual stimulation.

There are a variety of nerve endings that play different roles in the vaginal canal, with the idea of the ‘cervical orgasm’ being brought to life.

The understanding that the cervix may play a role in sexuality or even urinary function has meant increased incidence of supracervical hysterectomies, which means the surgical removal of the uterus with the cervix and ovaries being left intact.

Cysts and polyps

Nabothian cysts

Nabothian cysts are a normal finding and do not present a concern unless they are very large3,4.

Nabothian cysts are also known as mucinous retention cysts or epithelial cysts, and are benign features of the adult cervix, with multiple cysts possibly appearing at any given time.

These cysts present as similar to blisters since they are due to a blockage in the columnar epithelial cells of the cervix, which produce mucous. Cysts can be white or yellow, clear, from just millimetres to up to 4cm in diameter.

Polyps

Polyps might look like little dangling grapes and are generally benign, but need to be checked5.

How to care for your cervix

Regular pap tests for abnormal cells/HPV

It is recommended that you start getting pap tests or HPV blood tests no later than three years after becoming sexually active, or no later than age 21. These tests are to check for changes to cervical cells, usually due to HPV (human papillomavirus) infection6.

You can become infected with HPV just by skin-on-skin contact, and most people will be infected without knowing at some point. Everyone can get infected and now tested.

If you are over 65 or 70 and have had clear pap tests for the last three, you are considered out of the danger zone and don’t have to get pap tests anymore.

If you are over 30, you should be getting screened every one or two years, or at the recommendation of your practitioner.

There are guidelines in place for the different screening tests, and it’s better to be safe than sorry – cervical cancer can creep up quickly and show no symptoms7.

You often won’t know you have cervical cancer until it’s too late. If you have a weakened immune system or HIV, screening is recommended every year8.

Don’t douche

Douching is bad news for your cervix, as it washes away your good bacteria that sit all over your vaginal and cervical cells, fighting off bacteria9,10.

Study after study has found douching increases your risk of catching STIs, and that means it increases your risk of cervical cancer. HPV is an STI.

If you are sleeping around, use condoms

Naturally, the best way to avoid STIs is to never have sex (ha!). Make sure if you are having sex with more than one person between pap tests and STI checks, to use condoms.

If your options are not what they might be in life, you can protect your cervix with a diaphragm or cervical cap, as it keeps semen off your cervix directly and you can be in control of it: a male partner never needs to know it is even in there.

These protective sheilds can help to reduce STI and HIV transmission but are still being researched to see just how effective they are, considering the cervical cells seem to be the ones picking up most of the STIs.

Check out your own cervix

This might sound impossible, but it’s not, though to be fair it isn’t the world’s simplest operation either11.

You actually should know way more about your own junk than you do, and identifying early changes to your cervix may just save your life.

Self-examination doesn’t mean not getting a pap test, but check yourself out once or twice a year to keep on top of any changes, or just because it’s interesting! See our guide on self-examination of the cervix.

References

- 1.Scarpa B, Dunson DB, Colombo B. Cervical mucus secretions on the day of intercourse: An accurate marker of highly fertile days. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. Published online March 2006:72-78. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.07.024

- 2.Najmabadi S, Schliep KC, Simonsen SE, Porucznik CA, Egger MJ, Stanford JB. Cervical mucus patterns and the fertile window in women without known subfertility: a pooled analysis of three cohorts. Human Reproduction. Published online May 15, 2021:1784-1795. doi:10.1093/humrep/deab049

- 3.Harou K, Elfarji A, Bassir A, Boukhanni L, Asmouki H, Soummani A. Multiple Nabothian Cysts: A Cause of Cervical Obstruction. OALib. Published online 2019:1-5. doi:10.4236/oalib.1105212

- 4.Shroff N, Bhargava P. Giant nabothian cysts: A rare incidental diagnosis on MRI. Radiology Case Reports. Published online June 2021:1473-1476. doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2021.03.028

- 5.Pegu B, Srinivas BH, Saranya TS, Murugesan R, Priyadarshini Thippeswamy S, Gaur BPS. Cervical polyp: evaluating the need of routine surgical intervention and its correlation with cervical smear cytology and endometrial pathology: a retrospective study. Obstet Gynecol Sci. Published online November 15, 2020:735-742. doi:10.5468/ogs.20177

- 6.Poljak M, Cuschieri K, Alemany L, Vorsters A. Testing for Human Papillomaviruses in Urine, Blood, and Oral Specimens: an Update for the Laboratory. Humphries RM, ed. J Clin Microbiol. Published online July 13, 2023. doi:10.1128/jcm.01403-22

- 7.Dodd RH, Obermair HM, McCaffery KJ. Implementing changes to cervical screening: A qualitative study with health professionals. Aust NZ J Obst Gynaeco. Published online June 8, 2020:776-783. doi:10.1111/ajo.13200

- 8.Sachan PL, Singh M, Patel ML, Sachan R. A Study on Cervical Cancer Screening Using Pap Smear Test and Clinical Correlation. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing. Published online July 2018:337-341. doi:10.4103/apjon.apjon_15_18

- 9.Yıldırım R, Vural G, Koçoğlu E. Effect of vaginal douching on vaginal flora and genital infection. J Turkish German Gynecol Assoc. Published online March 1, 2020:29-34. doi:10.4274/jtgga.galenos.2019.2018.0133

- 10.Brotman RM, Klebanoff MA, Nansel TR, et al. A Longitudinal Study of Vaginal Douching and Bacterial Vaginosis–A Marginal Structural Modeling Analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology. Published online May 15, 2008:188-196. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn103

- 11.Casey PM, Long ME, Marnach ML. Abnormal Cervical Appearance: What to Do, When to Worry? Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Published online February 2011:147-151. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0512